The Art of the Stunt (Pt. 2)

Part Two: Brainstorming a Stunt

A stunt is an orchestrated public intervention: you hijack attention in an unexpected moment and redirect it towards an unexpected objective. These should lean closer to entertainment (e.g. The Portal) than utility (e.g. a planned retail pop-up).

In this three-part series, you’ll learn:

The categories of stunts, and which makes the most sense for you.

A framework for brainstorming a stunt. ← This post

How to maximize the success of a stunt.

When you’re deeply attuned to your audience, sometimes inspiration will strike and an idea for a stunt will come to you fully formed. But for those of us not so graced by God, it’s overwhelmingly more likely that we want to do a stunt but have no idea where to begin brainstorming.

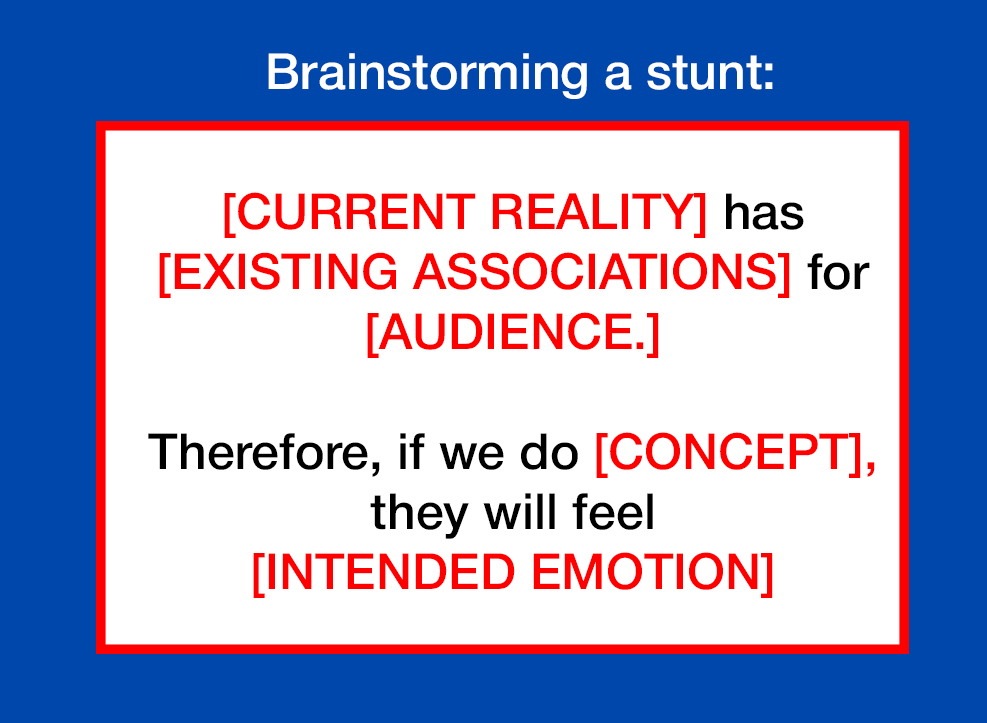

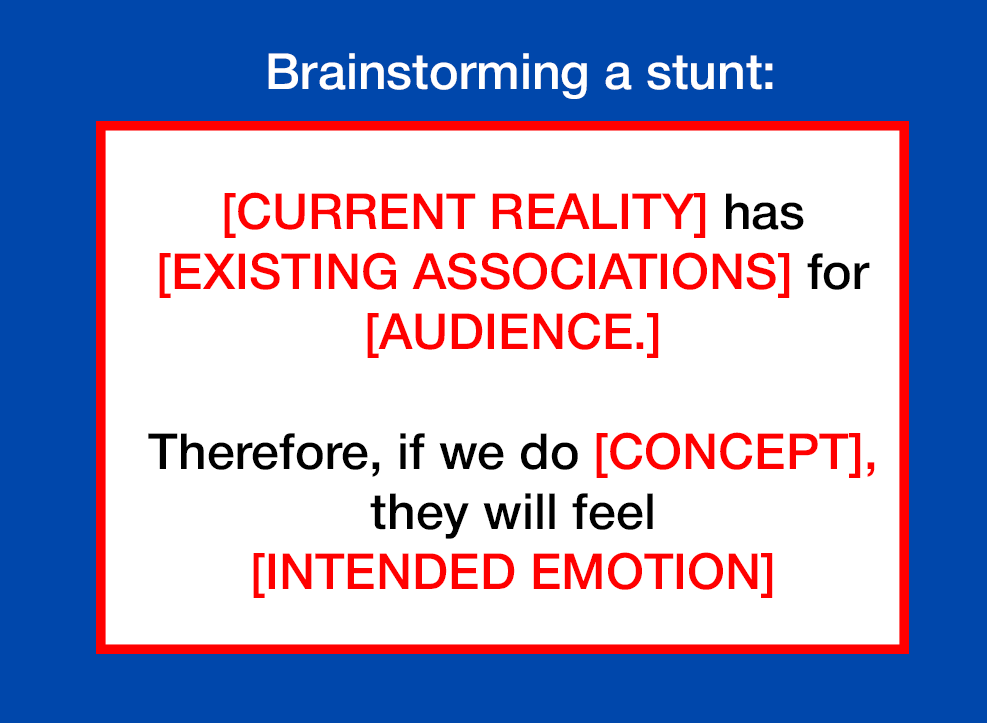

I’ve been studying legends of the form such as MSCHF, The Yes Men, and Eva & Franco in an attempt to find some common threads in their processes. Frameworks are ultimately just guardrails for intuition, so there’s only so much I can distill their art down to a science, but here’s one attempt at a formula:

You don’t necessarily have to brainstorm these sequentially! Inspiration can strike from any part of the equation, and the key is to think of each of these variables as prompts that give you the broadest possible surface area for creativity. If you don’t have an answer for one variable, you can get around a creative block by moving on to the next section.

Let’s break down each entry point:

I. Current reality: Stunts should exaggerate the spicy present.

II. Existing association: Hijack symbols that already mean something.

III. Define an audience: Build it where they are.

IV. Concept: Synthesize the most transmissible version of your idea.

V. Intended emotion: If they don’t feel something, you’ve lost.

I. Current reality: Stunts exaggerate the spicy present.

First, define your spicy present

Stunts are a public intervention, so by definition they require something for you to intervene with. The Yes Men refer to this as your “target”. This could be an entity (e.g. a company or a person) or it could be a norm (e.g. an expected behaviour or presentation of a thing).

Having a clear thesis statement grounds the rest of your brainstorming, so your stunt doesn’t try to say too much at once. Just write this out as a sentence on how the world currently operates:

Ramp hires Kevin from The Office as their CFO : “Manual expense reports are stupidly slow.”

Airrack makes The World’s Largest Pizza: “Pizzas serve 10 people.”

The Last Exorcism’s Chat Roulette striptease: “People can’t keep their pants on in internet chat rooms.”

Then, dial up the absurdity to its most exaggerated version

MSCHF’s employee handbook advises people to “Look for ways to exacerbate the Spicy Present, to extrapolate it into absurdity. It is not fiction or future; it is the accelerated and intensified present.”

You see this across all of their stunts, for example:

Key4All: “from Universal Basic Car to Public Universal Car”.

Current reality: “The sharing economy”

Most exaggerated version: What if thousands of people had their own individual keys to a literal shared car?

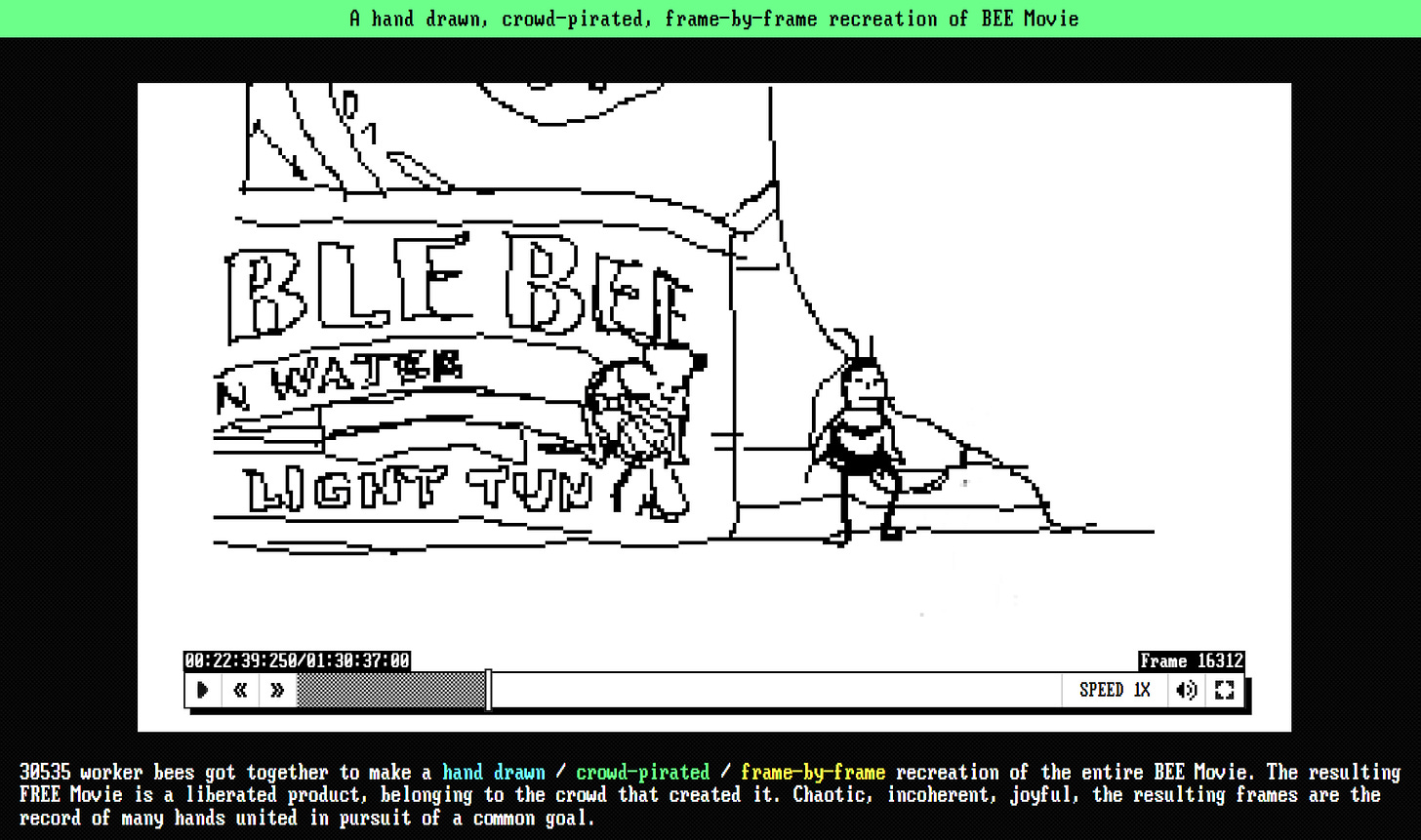

The Free Movie: “a distributed animated studio”, where “we are redrawing The Bee Movie by hand, frame by frame.”

Current reality: The Bee Movie was already a movie that had been adopted by the internet

Most exaggerated version: What if we could literally rebirth the movie through the internet? “Bees are collectivist and so are we. Join us as we liberate this movie one hand-drawn frame at a time.”

II. Existing association: Hijack symbols that already mean something.

As a general rule for getting attention, don’t make your life harder by starting from ground zero. The quickest way for an audience to build an emotional connection with your stunt is to hijack and subvert an association they already have. MSCHF refers to this as “cultural readymades,” and says, “Using materials that people have strong associations with = people will have strong reactions to your work.”

Some angles to approach this:

Characters: When Ramp built their stunt around Kevin from The Office, not only are they able to use him as a visual hook for their intended audience, but he also immediately acts as a shorthand symbol for their topic of “incompetence in the workplace.”

Expectations/Behaviours: Internet chat rooms have long been trying to solve “The Penis Problem.” “The Last Exorcism” teases that expected behaviour and then subverts it with a jumpscare.

Existing IP: Again, The Bee Movie already has a lot built up internet lore, so MSCHF took a shortcut to an emotional connection by building a stunt around it.

Phrases: I don’t think I’m chic enough to ever have placed an order at a restaurant by saying, “I’ll have the number two,” but The Yes Men have a classic stunt where they flip this line into a meal that is literally a “number two.”

News stories: When a bunch of idiots started throwing dildos onto the court during WNBA games, Polymarket tastelessly took their shot and put up a prediction market for it.1

III. Define an audience: Build it where they are.

In the same way that you might have an ideal customer profile (ICP) for the rest of your business, you need a clear idea of who your stunt is for. Remember that every part of this brainstorming formula is a variable — the same core idea can become something wildly different if you swap out one component and build it for Zoomer Girlies instead of for Boomer Finance Men.

Beyond basic demographic details (age, gender, employment, location, etc.), it’s worth considering:

Their relationship to your brand

Are they new to the category, customers of a competitor, current customers of yours, former customers, loyal customers, gift purchasers within the category, or category skeptics? This decision will also likely indicate whether you should do a prank, spectacle, or performance art.

The role you want your audience to play in the stunt

MSCHF’s employee manual teaches “Active participation > passive consumption”…“The truest audience for a reality TV show is its participants, not the viewers. Interactive absurdity creates distributed reality TV.2 Everyone’s a participant!”

I’d stretch their philosophy into a spectrum:

Stars (Active participation): Is your audience playing a core role in bringing the stunt to life, as with The Free Movie?

Co-conspirators (active consumption): Is there an opportunity for your audience to get involved in the stunt from afar, even if they’re not playing a core role in the stunt?

Witnesses (passive consumption): Is your audience just meant to watch, and hopefully share the stunt, as with the Severance Grand Station pop-up?

Where your audience is spending time

MSCHF often pushes back on the idea of “Build it and they will come”, and is far more confident that you should “build it where they already are.” Where is your audience already spending time, whether online or in-person? Which cultural subgroups do they belong to, and where do those people congregate?3 For example, Made On Verse’s Internet Bedroom, a stunt that turns your Spotify/Apple Music history into a blog that reflects your music taste, allegedly got its initial traction via cold outreach out to Kpop Fandom accounts on Twitter.

It’s also important to think about competing off-platform vs on-platform. A natively on-platform stunt (Instagram, TikTok, YouTube), will flatten you to compete against every other short-form vertical video. Competing off-platform (IRL, native web apps) is then a forcing function — you get to flourish on your own terms, but also have to be interesting enough to get organically posted back on-platform.4

Topics on their mind right now

Anthpo dropped some free game at ZCON, “If you’re a brand saying, ‘I want to make content for Gen Z boys,’ and you’re not watching 10 billion hours of Gen Z boy content, you’re out of the loop.” Brands can never be as online as their audience, so if you’re not working with a creator to lead your stunt, you should at the very least have a list of: extremely current news, inside jokes, in-group lore or language, and shared enemies. All of this can then be fodder for the previous variable, “Existing Associations”.

IV. Concept: Synthesize the most transmissible version of your idea.

Remix existing ideas

Good ideas beget good ideas.5 Become a student of the game, explore stunts that have already worked from directories like MSCHF’s drops, The Yes Men, Eva and Franco, or Actipedia, and then swap out variables to make it your own novel concept.6 We know great artists steal etc etc, but how?

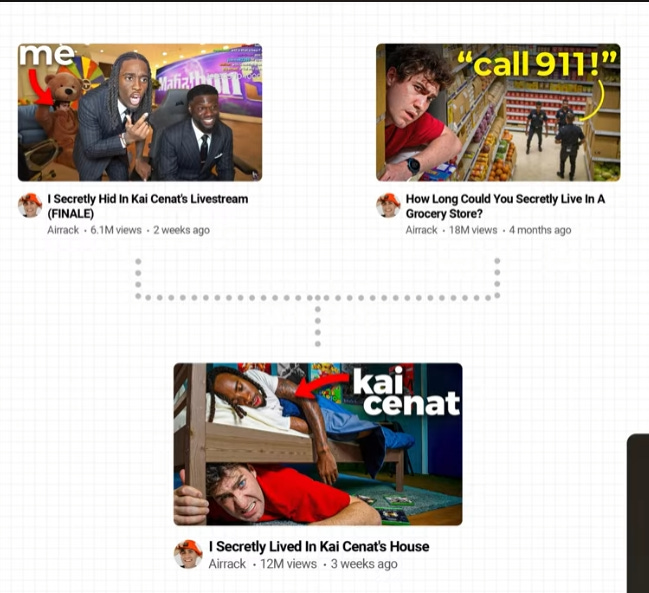

Jon Youshaie and Airrack dive into some great frameworks on remixing ideas (@19:20 but the whole interview is worth a watch), and there are three to call out in particular: find the intersection of winning ideas, synthesize and spin off winning concepts, and filter existing ideas through your brand:

Find the intersection of winning ideas

In “I Secretly Hid In Kai Cenat’s Livesteam”, Airrack tries to disguise himself and sneak into livestreams without the chat noticing that it’s him. In “How Long Could You Secretly Live In A Grocery Store?”, he tries to hide in a grocery store without getting caught by employees. Both of those concepts were clear winners (8M and 20M views respectively), so he found the intersection of them to create “I Secretly Live In Kai Cenat’s House.” (15M views)

You don’t have to take a swing at a wildly new concept — you can create something novel at the intersection of two already validated ideas.

Spin off winning concepts

Airrack’s newest rule is that he won’t make any video that doesn’t have the potential to become a series. It’s just too difficult and expensive to validate new ideas, and he wants his team to become the best in the world at formats that specifically work for him. He synthesizes the core part of a winning concept (e.g. “Sneaking in…”, “I Secretly Hid…”, “I Tried…”), and spins them off into new contexts.

Filter existing ideas through your brand

Early in his YouTube career, Airrack was known for burning hundreds of thousands of dollars on extravagant video concepts. But he learned that he can’t exclusively compete on spectacle, because that’s Mr. Beast’s competitive advantage. Instead, he realized that his competitive advantage was “mischief.” Now, he funnels winning ideas from other creators through that lens to find his own unique winners.

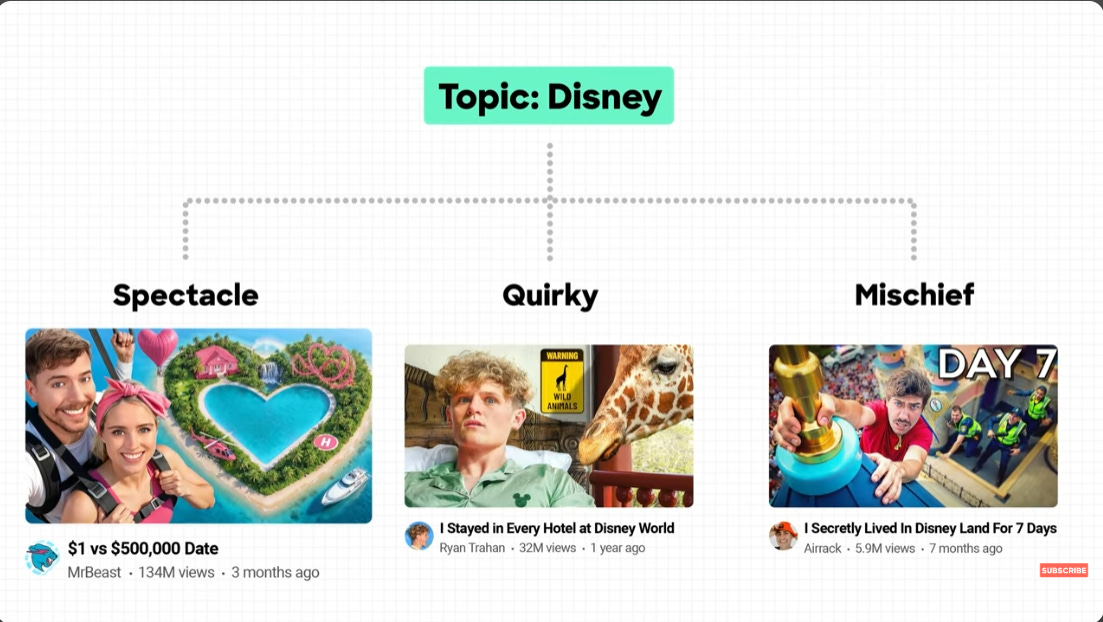

For example, if “Disney World” is your target or current reality, then:

Mr. Beast might filter it through his lens of “Spectacle” to create “$1 vs $500,000 Date”

Ryan Trahan might filter it through his lens of “Quirky” to create “I Stayed In Every Hotel at Disney World”

Airrack might filter it through his lens of “Mischief” to create “I Secretly Lived In Disney Land for 7 Days.”

Define your concept in one sentence, three sentences, and five sentences.

Gabe Whaley, MSCHF’s founder, says “an idea…has got to slap in one sentence. It’s got to slap harder in three. [Only five] when the crowd takes it.”

Your idea needs to be intrinsically simple for it to accomplish any sort of meaningful scale online — you only have a millisecond to win someone’s attention off a thumbnail, email header, or video hook. But a great idea, one that can be stretched to “five sentences”, accomplishes simplicity while also harbouring enough depth for the audience to project their own interpretations onto it.7 I wish there were more stunts that accomplished this.

V. Intended emotion: If they don’t feel something, you’ve already lost.

You’re at the end of the equation. Revisit your entire idea through the lens of the emotion that you’re trying to elicit. Is your stunt…

😂 LOL - Hilarious

😡 WTF - Outrageous

😲 OMG - Incredible

😍 AWW - Heartwarming

Shaan Puri synthesizes this well (@3:06), borrowing frameworks from both Jonah Peretti and Steven Bartlett:

Imagine “Jenny in her bed,” a stand-in for a casual viewer loafing around at home, mindlessly scrolling social media. Unless a piece of content gets her to stop, think or feel something, and then share it with a friend,8 then there was no reason to make that thing in the first place. When you’re optimizing for reach, work backwards: choose the desired reaction you want, then make the content to provoke it.9 And then watch it back and ask yourself, do you really think you’re getting the emotion you wanted? If not, recreate the thing until it does.

Once again, even if you keep the other variables of the stunt constant (e.g. “Current Reality,” “Existing Associations,” “Audience,”) you can get to a wildly different stunt when you decide to optimize for, say, humour instead of outrage. Use this to brainstorm permutations of your concept.

I hate to keep harping on the Ramp CFO stunt, but it’s a recent one with a clear narrative. Through the lens of this equation, a very basic interpretation of the stunt might be something like:

[Most finance teams are archaic], and [Kevin From The Office is a good representation of workplace incompetence] for [White Collar Millennials who are now in some position of power at a tech company].

It’d make them [laugh] if we [got Kevin to do a livestream race against our expense management software.]

Make this equation your own! Frameworks are helpful because they’re modular. You can take the parts that work for you, and ignore the parts that don’t. I don’t think that all of my favourite stunts apply perfectly to this outline, but I do think it’s a helpful onramp for your brainstorming time. The key is to maximize your surface area for creativity. At any given moment, a good idea is a three millimeter change away from being a great idea.

Thanks for reading! I write about branded entertainment, exploring how brands and startups become media companies.

This post is part of my weekly strategy series, which is typically reserved for paid subscribers. If you enjoyed this, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or sharing it with a homie <3

Technically the original act was a stunt by some crypto group, and it’s unclear who actually put up the prediction market on Polymarket.

If you were on Tech Twitter in 2023, then the ~48 hour saga of Sam Altman getting removed from OpenAI was a perfect example of this. Even more true if you worked at OpenAI during that absurdity. Information leaking in real-time, not knowing what’s what, piecing together first person tweets to form some coherent narrative. It was truly distributed reality TV.

Yes Theory did an all-time stunt in 2018. They were able to weaponize r/mildlyinfuriating, a hyper-specific subreddit that already congregated the sorts of people who would find their stunt shareable.

You can also just hire third party clippers.

Gabe Whaley says that MSCHF has a full-time hire whose entire job is to create a curriculum of interesting inputs for their team.

The Last Exorcism’s Chat Roulette Striptease took inspiration from Eva and Franco’s “No Fun,” in the same way Ramp’s CFO stunt took inspiration from Severance’s Grand Central Station stunt.

“...when a body of work that I have nurtured and cared for is thrust out into the world, the umbilical chord is cut and naturally everyone begins to project the work onto themselves. The meaning is morphed, personalized and applied to each individuals’ own life” - charli xcx

This is doubly important for IRL stunts. Your moment has to be so emotionally charged, that people are willing to pull out their phones and record an Instagram Story. Everyone’s looking for an excuse to show how interesting their lives are, and you can weaponize that with a stunt.

This is obviously a soulless approach to creating all art. But if you’re designing a stunt explicitly for awareness, it makes sense to optimize with the end in mind.

The framwork of exaggerating the spicy present into absurdity is brilliant. The Ramp CFO example really shows how hijacking existing cultural readymades can give you instant recogntion without needing to build context from scratch. I also appreciate how you emphasize that participation beats passive consumption, turning the audince into co-conspirators makes the stunt feel more alive and shareable.