The Art of the Stunt (Pt. 1)

Part One: Taxonomy of a Stunt

A stunt is an orchestrated public intervention: you hijack attention in an unexpected moment and redirect it towards an unexpected objective. These should lean closer to entertainment (e.g. The Portal) than utility (e.g. a planned retail pop-up).

In this three-part series, you’ll learn:

The categories of stunts, and which makes the most sense for you. ← This post

How to maximize the success of a stunt.

It feels like everyone is stuntin’ nowadays.1 But stunts aren’t a monolith, and if you play stupid attention games, you win stupid attention prizes.2

What are we actually talking about when we refer to something as a “stunt”? And, more importantly, what are we actually trying to achieve for our businesses? I’ll be the first to admit that taxonomies can feel masturbatory — a way for pundits to make themselves feel good and smart by unnecessarily organizing information. But if you’re going to spend time and money on a marketing stunt, especially with incremental dollars that could have been spent on a more measurable acquisition channel like paid ads, upfront precision is important.

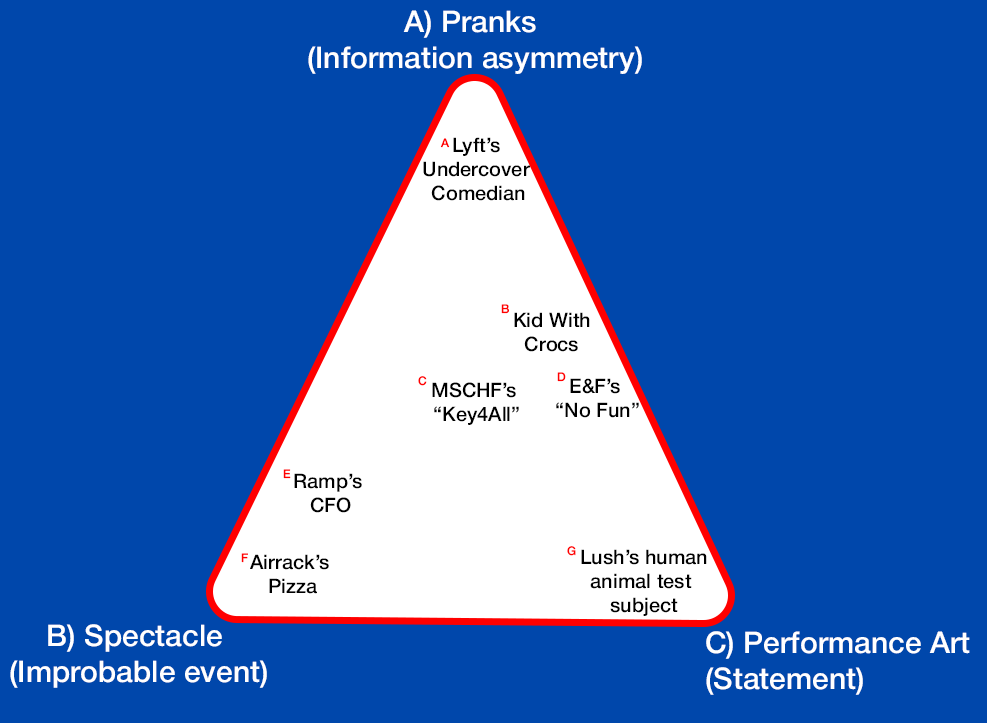

Different types of stunts map to different business objectives, and can be a footgun if you pursue them blindly. Let’s map them onto a spectrum of three distinct but related points of a triangle:

Point A: Pranks optimize for pure awareness through information asymmetry

Point B: Spectacles optimize for brand narrative by engineering an improbable event

Point C: Performance Art optimizes for depth by making a statement

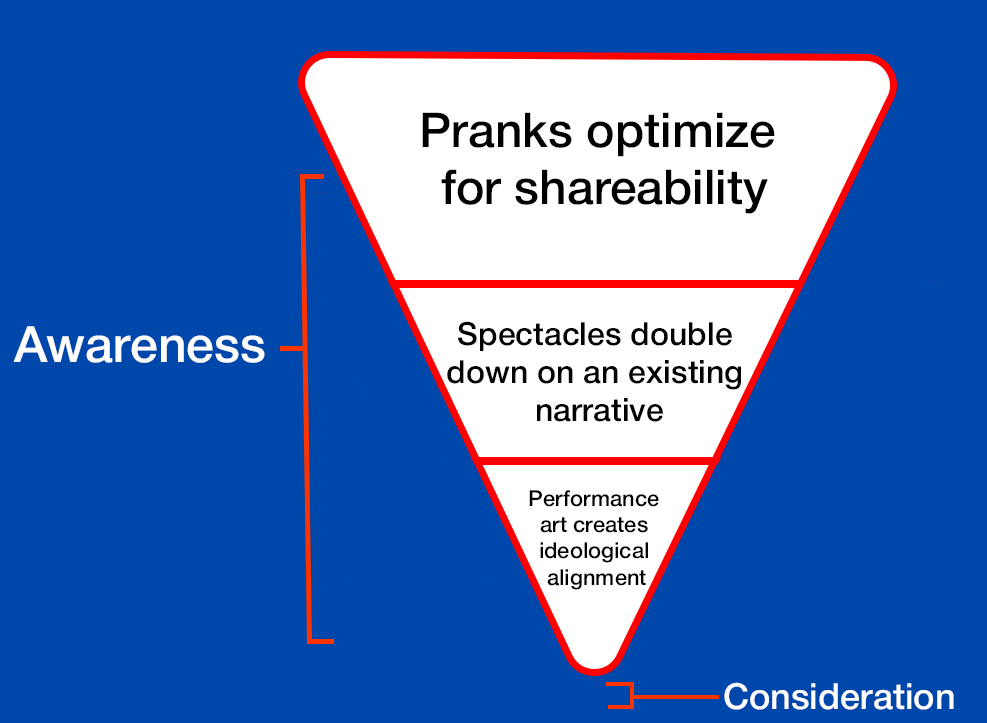

Stunts are almost exclusively a top-of-funnel activity. They’re designed to drive awareness, not purchasing decisions. But these three categories represent a progressively deeper funnel of their own:

Pranks are at the top as a pure awareness play for net new audiences, spectacles are slightly lower funnel because they double down on an existing narrative, and performance art is the lowest funnel stunt because it draws a political line in the sand around your brand’s point of view.

Before you start brainstorming a stunt (which I’ll cover in next week’s post), you need to clarify why you’re running a stunt and which type of stunt makes the most sense for your business objective.

A) Pranks: Optimizing for pure awareness through information asymmetry

Pranks are funny or shareable because you have information that the “victim” does not: an unwitting participant enters an interaction that you control, and the entertainment comes from the reaction or the reveal. These work best for pure awareness because pranks clip well on social platforms and have high entertainment value with very little context required.

Pranks are cheap, high-variance, and reaction-driven, which means they’re uniquely suited for content volume and shareability. I’d suggest trying a prank-style stunt if:

You’re trying to build a recurring content format. Again, the most entertaining moment of a prank is the reaction or the reveal. So once you find an angle that works, you can just find new participants to farm over and over.

You’re experimenting with a small budget, and your sole objective is shareability and/or cheap CPMs.

You want interactivity to play a core part in the stunt. Pranks are a good opportunity for you to interface directly with people.

You have low risk tolerance. Pranks can be extremely offline and localized — if it flops, there’s a low opportunity cost to just not post the content anywhere.

Branded examples:

B) Spectacles: Optimizing for brand narrative by engineering an improbable event

Spectacles are perhaps the most purely distilled version of a stunt, and often the thing that people are actually referring to when they colloquially say “stunt.” They’re an opportunity to orchestrate something so absurd or exaggerated that you can interrupt people and redirect their attention elsewhere. These can, of course, work with a net-new audience, but are often slightly more down-funnel than pranks because they’re most memorable when there’s some degree of brand familiarity.

Spectacles are often expensive and long-lasting, best for scale or narrative control. I’d suggest trying a spectacle-style stunt if:

You’re trying to build a single artifact that you can point to, such as an IRL moment or a longform piece of media. Unlike pranks, which can be low-gravitas or repeatable, a spectacle’s entertainment value comes from its one-off magnitude. A good one becomes a part of your brand mythology that fans feel a part of forever (“remember when they did X?”)

You’re solidifying awareness among semi-warm audiences. Pranks are a good way to introduce you to strangers. Performance art pushes people towards true believers. Spectacles sit in the middle: They give the casually aware something to get more curious about. They can solidify an existing brand narrative or combat clear misconceptions. They’re an opportunity to put a stake in the ground around who you are and are not.

You’re in a category where proof-of-scale matters. A large enough spectacle is a display of credibility. Just be careful to be precise about who you’re showing credibility to.5

You have a B2B audience and/or you’re trying to impress other advertisers. The agency award shows are apparently a big corrupt circlejerk that peaked a decade ago, but if you for some reason really want to win one, other advertisers seem to go crazy over a very particular type of spectacle.

Branded examples:

C) Performance Art: Optimizing for depth by making a statement

Performance art dramatizes or exaggerates a philosophy that your brand holds dear. These are still an awareness play, but, again, I’d argue they’re lower in the funnel than pranks or spectacles. When done well, this type of stunt allows you to contrast your brand’s point of view against some sort of antagonist, which sparks more of an emotional connection than a prank or a spectacle. These are more likely to move customers into the consideration phase of the buying journey.

Performance art is ideological and polarizing — best to build depth and conviction. I’d suggest a swing at performance art if:

Your buyers have ideology as a core part of their purchasing decision. This works well for brands who lean on marketing angles such as: Us vs Them, critiquing the status quo, or mobilizing alongside a social cause. Just make sure you’re punching up, not down.

You’re optimizing for earned media or cultural authority: op-eds, legacy media commentary, video essays, or TikTok reactions. If you have something truly novel to say, people will use the opportunity to mine you for their own content.

You have a significant budget to take a big swing, and a high enough risk tolerance in case the stunt doesn’t land. Nothing’s more painful than trying to make a point and then getting dunked on.

Branded examples:

If you want to come up with a good stunt, you need to become a student of the game. Stunts are often a remix of something that came before them, like how The Last Exorcism learned from Eva & Franco’s “No Fun”, or how Ramp’s CFO stunt learned from Severance’s Grand Central Pop-Up. A nuanced taxonomy, then, also helps you to become more precise in your hunt for inspiration for your own stunt. For example, if you know that your business needs to make an ideological statement to stand out in a crowded market, you want to specifically brainstorm on top of existing performance art examples.

Here’s a Deep Research query I sent to ChatGPT to find some good inspiration for branded performance art:

I’m looking for examples of brands doing “performance art” stunts. Based on the below context, could you please find me examples of BRANDED “Performance Art” stunts? I define performance art as “Performance art dramatizes or exaggerates a philosophy that your brand holds dear. These are still an awareness play, but I’d argue they’re lower in the funnel than pranks or spectacles. When done well, this type of stunt allows you to contrast your brand’s point of view against some sort of antagonist, which spurs more of an emotional connection than a prank or a spectacle.”

Could you please find me ten good examples over the last 5 years of a brand doing this well?

This post was concerned with the taxonomy of a stunt, and deciding which type of stunt makes sense for your business. Next week, we’ll get into some more theory around how to brainstorm a good stunt.

Thanks for reading! I write about branded entertainment, exploring how brands and tech companies can build better media properties.

This post is part of my weekly strategy series, which is typically reserved for paid subscribers. If you enjoyed this, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or sharing it with a homie.

Tech has a bad reputation for dehumanizing things. But high-effort is inherently anti-slop, so stunts are a medium with baked-in proof of humanity. Now that Ramp has reminded people that marketing B2B SaaS can be fun, I suspect that many other deep pockets will follow suit (in the same way that no one was doing a high-production launch video, and then suddenly everyone was doing a high-production launch video.)

Everyone on my Twitter timeline seems to be piling on Roy and the Cluely team this week, but tbh I’m an irrational Cluely apologist. They can be pure brainrot, but they’re sharp yutes and I hope they figure it out. Whether you like them or not, no one can deny that they’re pushing the metagame forward. It’s just up to you to learn the right lessons from their insane marketing.

This one is an edge case, admittedly. But I do think that quiz set-ups where a user inputs information in anticipation of some reveal is a type of stunt. Spotify Wrapped, for example, follows a similar playbook. Even if it’s not a “prank” in the jump-scare way that it might be colloquially understood, this format is hyper personalized, shareable, and leans on the reaction or reveal.

What’s interesting about the Severance Grand Central stunt is that it’s possible Apple had a meta target here. There has been a lot of whispering about Apple being bad at marketing its fantastic slate of original programming, and I wonder if that led to it losing bids on competitive packages. This stunt was obviously primarily for Severance, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was also a signal to the market.

Admittedly this is a hard one to categorize! There’s no “statement” in the way you might usually expect from performance art (serious, politicized, or ideological). But Anthpo’s certainly making some point here (irony, silly-maxxing, go outside). I do think it’s a good example of stretching the performance art format. I’m going to write a case study on this stunt next week and we can dive into more details there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPz7LCybSNk

this is great