Beyond Niches: An independent media business should be a never-ending essay

Between my time at Substack and Shopify, I’ve probably worked with something like 5,000 internet businesses to help define their voice online. Here’s a framework that continues to help me.

You pick a niche to become legible. It makes sense! In the infinite content deluge of the world wide web, if you try to speak to everyone you end up resonating with no one. But no one who is compelled to share their opinions online wants to be flattened into a single “vertical”. An IG tagline like “your marketing bestie” isn’t an expression of one’s singular artistry; it’s a projection of how you think the internet wants to perceive you. The balance, then, is to constantly oscillate between legibility and illegibility. You do this by designing your independent media business like a never-ending essay.

An essay is a clear question that unfolds in surprising ways—the doorway to your world should be clear, but the room one enters should be surprising. Kanye West would never have been able to release Yeezus (the best album of all time) if he wasn’t a soul producer first. Addison Rae would never have become a megapop star if she wasn’t a TikTok dancer first. Legibility earns you the permission to be illegible. Find a question that you explore as naturally as breathing, and then bring your audience along as you compound it into social capital over the course of decades.

To write a never-ending essay is to build a lens through which an audience can view your world. It has to be wide enough that it can sprawl across categories, but clear enough that people can reasonably expect what they’re getting themselves into. Four parameters shape that lens:

I. Channel: The medium and platform you choose to build on

II. Concept: Your core thesis

III. Substance: The craft itself

IV. Spectacle: Your ability to create recognizable moments

The key is that all new media businesses have some proportion of these four traits, but you can do surprisingly well in a competitive category by leaning into one that your competitors do not.

I. Channel: The medium and platform you choose to exist on

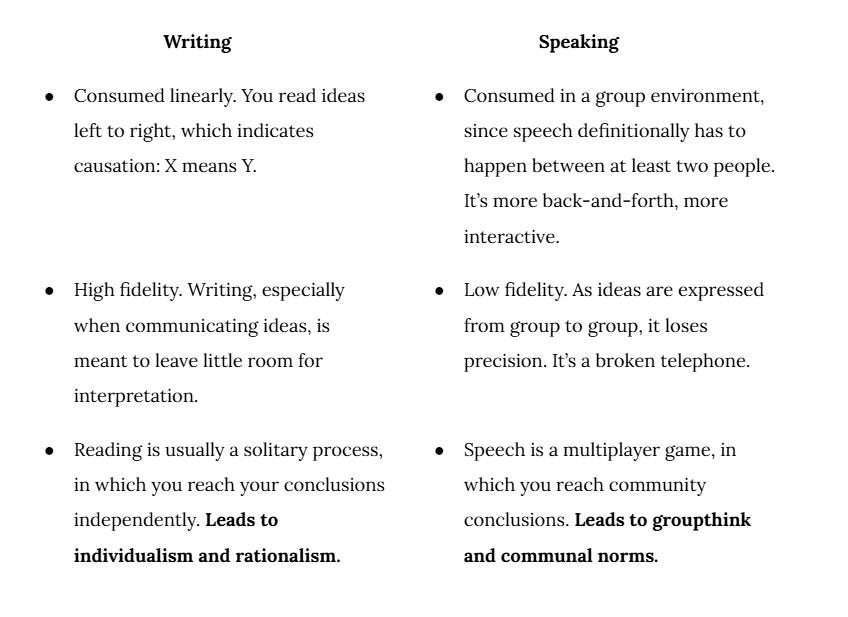

McLuhan’s “the medium is the message”, perhaps the most famous media framework by perhaps the most famous media theorist, is typically applied to understanding platforms or technologies. He explains that the evolution from spoken communication to written communication, irrespective of any specific content that was being communicated, directly led to individualism and rationalism. He theorizes that this is because of the way writing as a medium is inherently ingested. Compare:

All this to say that, even before considering the content itself, the medium you choose will shape the ways in which people process your work1. There are, of course, pragmatic reasons to double down on any particular medium or media platform: the speed a platform is growing, the size of an existing audience there, your preferred medium of communication. But if we know that the medium itself is bound to a particular mode of consumption, then there are two approaches to choose your platform:

A) Choose a platform whose consumption patterns are complementary to your core thesis. For example, if your media revolves around explanation or argument, build on a platform where that is the primary mode that people want to be in while they’re there.

CASE STUDY: Subway Takes is winning via a complementary platform

Instagram: hot people, no hot takes.

Twitter: ugly people, extremely hot takes.

TikTok (the lovechild): hot people and hot takes.

New York, aka Sean Monahan’s TikTok city, is where onlineness takes its physical form. So, Subway Takes, a TikTok show where niche NYC celebrities give niche takes while riding the metro, is riding the perfect tailwind: it packages the “hot people giving hot takes” pattern that had already existed on TikTok into a repeatable and recognizable media business. It’s an incredible media business purpose-built for the existing consumption patterns on TikTok.

B) Choose a platform whose consumption patterns present an arbitrage for your core thesis. Take advantage of a mispriced marketplace of attention. For example, if a platform is primarily filled with spectacle or personality-first content, there may be an opportunity to stand out as a pattern interruption through media rooted in narrative and storytelling.

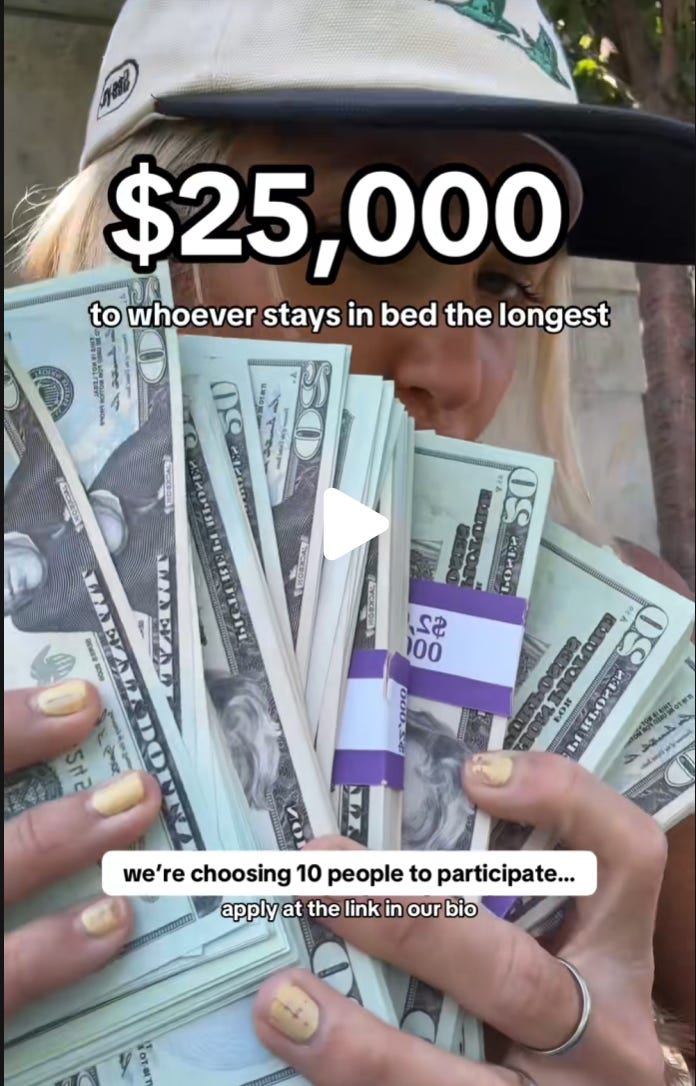

CASE STUDY: Cozy Earth is winning via a platform arbitrage

TikTok Live has a reputation for being filled with slop: people shilling low-quality products via their TikTok Shop, or personalities shamelessly monetizing audience interactions. Cozy Earth, a bedding and loungewear company, used this as a mispriced market: people were paying attention to TikTok Lives, but there just wasn’t any good narrative content there. So they created a “Bed Rot Challenge”, a live-stream reality show where contestants couldn’t leave their bed for five days straight. In a sea of attention-baiting dopamine hits on TikTok Live, a narrative-driven reality show feels like a breath of fresh air.

II. Concept: Your core thesis

“People don’t have ideas, ideas have people.” If ideas spread like a contagion, then building an independent media business is akin to isolating a new mindvirus. You identify a dormant idea or question or feeling that floats in our collective unconscious—ideally one that a particular cohort is already vaguely exploring but hasn’t yet been able to name—and then you articulate it in a way that rallies audiences around your mission. Ideally your concept has a trend or a macro change that may act as a tailwind, can be easily explained from friend to friend in a sentence or two, and is a question that you can explore for years not months. This is ultimately a flattening of your thesis or question into a digestible and transmissible package, which then shapes the rest of your media business, from aesthetics, to monetization, to distribution.

Some miscellaneous concepts that I like:

Fashion Neurosis with Bella Freud: Questioning the link between fashion and identity.

Cluely: Cheat on everything.

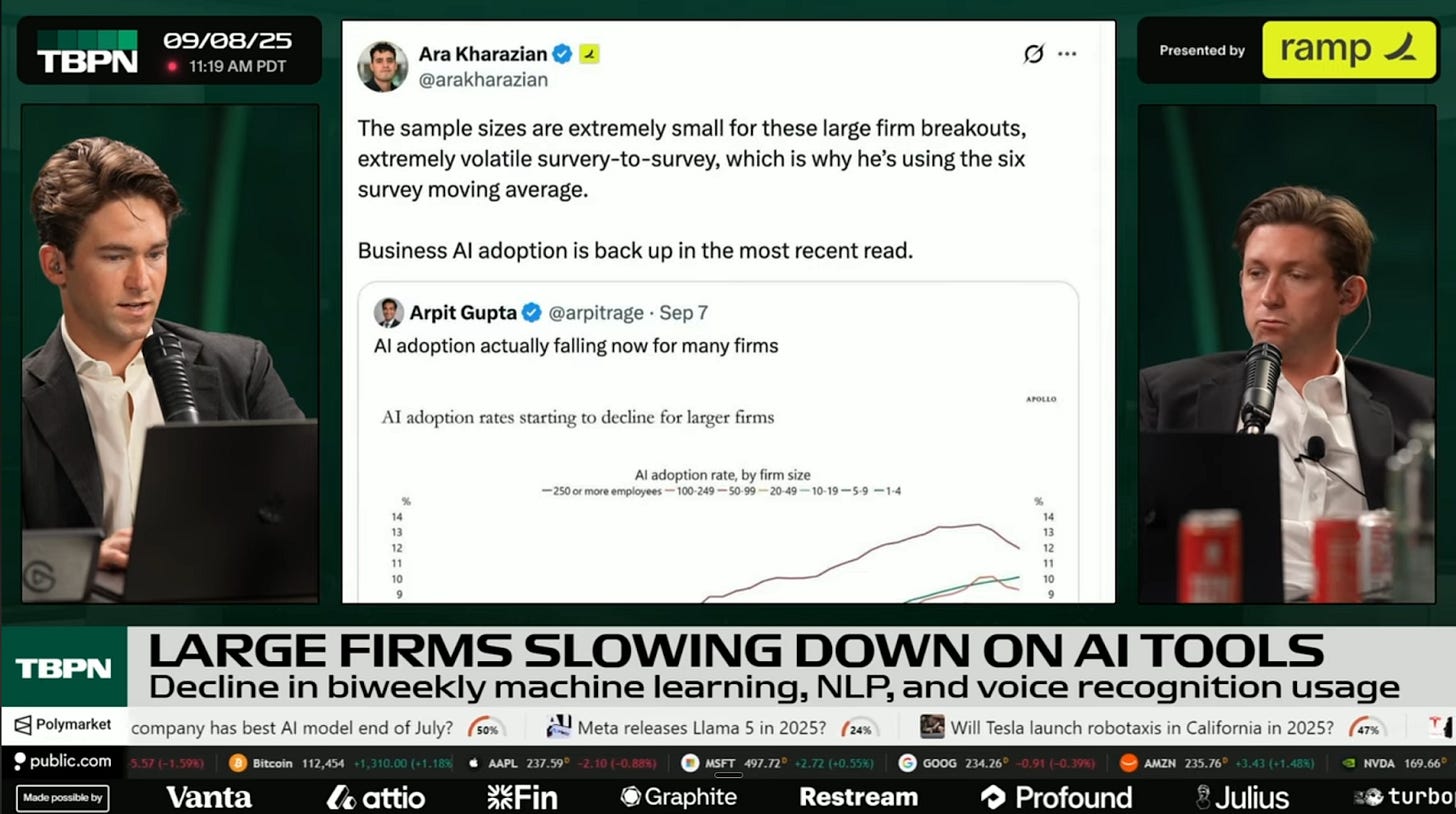

CASE STUDY: Technology Business Podcast Network (TBPN) wins on Concept

TBPN believes that tech is a spectator sport, and it has quickly become “tech’s daily show”. They stream everyday from 11am-2pm PT, and line up industry insiders to comment on all levels of the tech industry: big announcements from megacap companies, niche gossip2, and everything in between. The tech industry has long made Twitter its home for in-group chatter, dunking on each other’s businesses or praising tactical decisions. The genius of TBPN’s concept is they packaged what was already happening into a format that has decades of proof behind it—a daily talk show. That core concept then informs everything else about the show:

Aesthetics

Your visual form should be a mechanism that amplifies your core concept3. The aesthetics of TBPN are recognizably designed to look like cable news: the chevrons, the rolling sponsors, the camera cuts. The show originally had “Technology Brother” in the title4, a flip on the slur of “tech bro”, which the hosts consciously elevate with their slicked back hair and formal wear. They seem more like status-seeking Wall Street bankers (complimentary) than hoodie-donning tech dweebs. All of it blends together to present a new image of what a tech pundit can look like, and as soon as you see the visual presentation of the show, even with zero context on its broader concept, you’re halfway to understanding what’s going on.

Monetization

There’s no need to experiment with paid subscriptions or branded products when the monetization strategy for a daily show is already tried and true: ads. They, however, have the benefit of dodging the standard podcast brand deal strategy of pausing the show at the halfway mark to do a 30 second midroll sponsor read because they have an egregious amount of sponsorship capacity in their rolling ticker. Any other podcast with that much blatant ad space would be insulting to the viewer, but within the confines of their concept, it hilariously adds to the effect.

Distribution

If TBPN’s concept is to monitor the tech industry as though it’s a spectator sport, and top tech talent is now getting athlete level contracts, then you can imagine a whole host of marketing stunts that work within the context of their concept: treating job changes as though major athletes are switching teams, tracking org charts as though they’re a betting line, or being on the ground for game-day interviews at major events. The best part about a concept that fits into the habits of an existing in-group is that they feel like they’re in on the joke, which is an easy opportunity for your audience to get involved with your marketing.

III. Substance: The craft itself

Not to be all “tech-guy-from-Toronto”, but, alas, as a tech guy from Toronto, Drake explains Substance best on Pound Cake / Paris Morton Music 2: “Like I didn’t study the game to the letter/And understand that I’m not doing it the same, that I’m doing it better”. It’s not worth spending too much time here because Substance is a parameter that can vary wildly depending on your craft of choice, the type of business that you’re trying to build, and your natural talents. But broadly there are two ways to approach “doing it better”:

Do you have the sauce?

Are you good at what you do? Do you have a unique voice, a novel perspective, some charisma? Are you doing the equivalent of piano scales for your craft? Substance is the three stages of mastery in the Japanese martial arts concept of Shuhari:

Shu (study and adhere to the rules, the fundamentals)

Ha (detach from tradition, explore)

Ri (can you transcend the rules and break them in the quest for true mastery).

Can you push the medium forward?

Instead of competing head-on with the craftspeople who came before you, you can often win on “substance” by combining a few crafts into something new5. Drake combined RnB and Hiphop to create a sadboi version of rap music that pushed the entire genre forward6. TBPN combined the high-production value of a TV set with the instant pulse-check of Twitter to create a new type of live show.

CASE STUDY: Dwarkesh Patel wins on substance

Dwarkesh Patel’s “deeply researched interview series” is in the middle of a meteoric rise, flying from 23,000 YouTube subscribers in September 2023 to just under 1M two years later. He’s firmly a character in the tech industry, but calling it a “tech podcast” would be reductive: he spends weeks preparing to interview world-class experts on everything from history to AGI to biology.

You would think that podcasting, especially in the broader tech industry, was tapped dry years ago. But Dwarkesh says it best himself (@ 41:40): “Even though it seems that there are a lot of podcasts, it’s just, like, not that competitive. In the sense that there’s not that many people who treat this seriously as a craft, who’re doing this full-time, who, like, really care.”

Dwarkesh has booked some of the biggest names in tech, Mark Zuckerberg, Satya Nadella, a co-sign from Jeff Bezos, and he seems to credit much of it to just asking better questions than his peers. Podcasting, researching, and interviewing are all a craft to him—he doesn’t need to win on concept or spectacle because he’s just pushing the core substance to a new level.

IV. Spectacle: Your ability to create recognizable moments

A spectacle is a device that serves to amplify or exaggerate your concept. It’s often confused with having a “gimmick”, but I think that’s cope from people who can’t come up with good concepts. A gimmick is a device designed to capture attention without an attachment to an underlying concept7. It’s an attempt to differentiate your media in a cheap way that doesn’t actually amplify or relate to your core question.

To be clear: chasing virality is obviously not a sustainable way to grow a media business. It either becomes a crutch for a bad product, or it forces you to sacrifice the integrity of your thesis for a short-term win. Spectacles, however, are an opportunity to bake mechanisms or moments of virality into your product in ways that actually help to answer your core question.

CASE STUDY: “Hot Ones” is a Spectacle, “Cold As Balls” is a Gimmick.

Hot Ones, “the show with hot wings and even hotter questions.”, has celebrities answering progressively spicier questions while eating progressively spicier wings. The spicy questions are the concept (“how do we get the most honest celebrity interviews possible?”), and the spicy wings are the spectacle. There’s only so much PR training you can retain when your face is melting off. It’s an incredible example of a spectacle that actually serves the underlying concept—the spicy wings are a mechanism8 to better answer the podcast’s core question.

Cold As Balls, Kevin Hart’s show where celebrities get into an ice bath during their interview with him, in comparison feels to me more like a gimmick. In theory, he had an opportunity to take Hot One’s lead, and escalate the interview as the guest gets progressively more submerged in the ice bath. But the execution doesn’t come through, and ultimately it feels more like an attempt at clipfarming funny celebrity icebath reactions.

An essay is an attempt to figure something out. The reality is that there is never going to be a real map to become Kanye West, or Addison Rae, or whichever generational media personality/business you can think of. No audience ever elevates the same media business twice, for it is not the same media business and they are not the same audience (or something like that.) My argument is simply that if you’re picking a niche in an effort to be understood, then there’s a far better way to do it. Channel, Concept, Substance, and Spectacle are four levers that help to bring your audience along on an illegible journey towards a legible goal.

The Washington Posts’ “Creator Hub cohort” plainly describes this as, “our fashion critic will bring her analysis in more visual formats (you’ve got to see the clothes)”. (of course)

Elon used this line before he fired Parag from Twitter https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-63098117

Fashion Neurosis is another good example of this, where you can immediately visually understand that the guest is in a therapy session.

“TB” in “TBPN” used to stand for “Technology Brother”, but apparently it now stands for “Technology Business”. I think this is because of a trademark that is hilariously owned by a friend of mine.

If you’ll humour me with a long wandering aside, I’ve been studying T.S. Eliot lately, and it’s fascinating to see how his poems take shape through other mediums. Take this rhyme scheme in “The Love Song Of J. Alfred Prufrock” as an example:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

His rhyme scheme isn’t a classic A/B/A/B or A/A/B/B. It’s actually A/A/C. “You and I” rhymes with “against the sky”, but “upon a table” is a surprise, a riff, a pattern interrupt. In this way, among others that aren’t worth getting into right now, he’s creating a new form within his poetry by borrowing from the surprising musicality of jazz. Similarly, take this passage which follows immediately afterwards:

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question ...

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

Eliot is taking us on a very clear visual journey here in the first half of the stanza: a lonely walk observing a bleak city of some sort. And then he borrows from film form, and effectively jump cuts to a new environment: why are we suddenly in a room, an art gallery of some sort presumably, talking of Michelangelo?

He’s a student of the game: by combining patterns from film and jazz, Eliot’s poetry feels like a fresh take on an old craft.

The other genius of the spicy wing mechanism is that it inherently builds in viewer retention. You have to watch until the next spicy wing, and the next, and so on, because you want to see how the temperature of the interview evolves. It’s a qualitatively different show as the wings (and questions) get progressively spicier.

Ooooo this post is solid and I need to think about my never ending essay for awhile