Game Tape #4: Software as a lead magnet

Cluely son or Verse daughter?

Game Tape is a weekly series where I highlight lessons from a new media property. Notice an interesting moment you want me to talk about? Hit reply and let me know.

Somewhere in the multiverse, there’s a timeline where the tech industry got its “distribution” hard-on from Verse’s “Internet Bedroom” instead of Cluely’s launch video. One year later, the pendulum is swinging and tech is finally realizing that not all attention is given equally. Attention stolen with ragebait leaves us embittered, jumping into the comments section to prove someone wrong on the internet; attention earned with active participation makes a big world feel small, connecting us to micro-communities that we never could have found in-person.

Jamie Cho’s fantastic Internet Bedroom stunt from September 2024 is a great example of the latter. Back in 2017, it was a novel idea to give away a self-contained media product as a top-of-funnel “lead magnet” for your business — you could generate leads by offering some resource in exchange for a prospect’s contact information. It sounds embarrassingly basic now, but one of the most successful ad campaigns I once ran for an ecommerce brand would just point traffic to a free eBook with “10 tips to sleep better.” People would sign up for my email list to access the document, and then I would slowly upsell them on a related paid offer over time.

As coding models improve, and building software1 becomes as simple as writing a PDF, the best lead magnets will be digital experiences, not downloads.

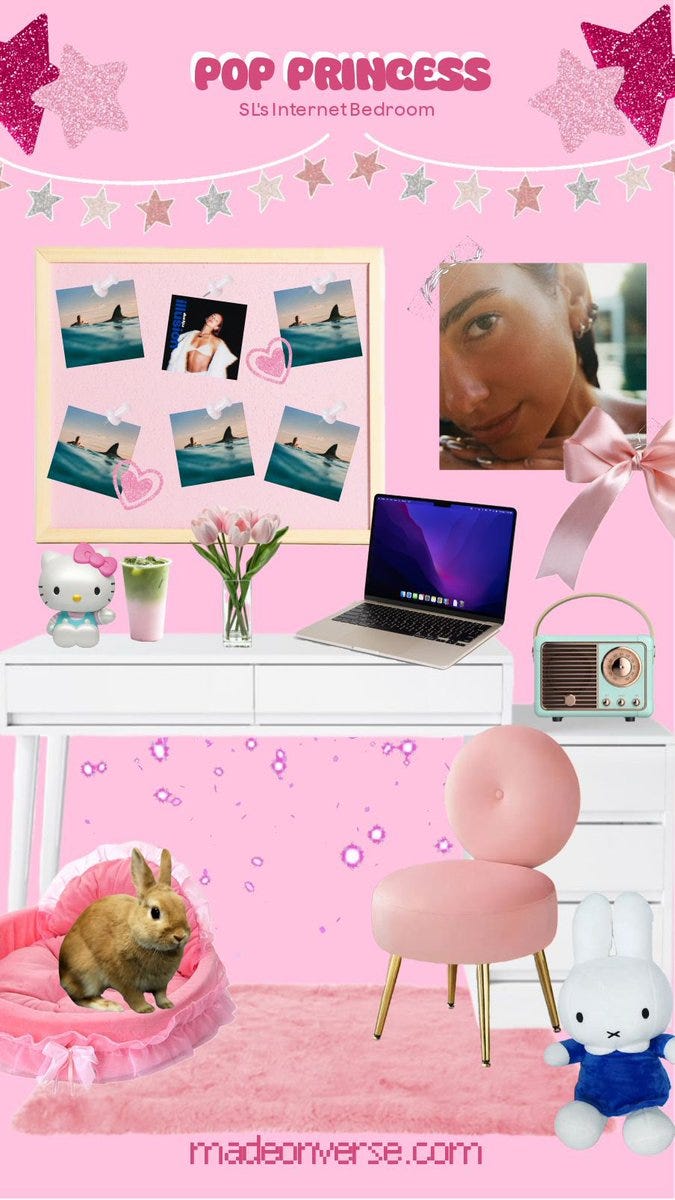

Verse2 was a “creative platform where users build personalized digital collages.” You can see a video of the Internet Bedroom in action here, but the gist is:

You connect your Spotify or Apple Music account.

Verse generates you a personalized mini-site, decorated in the colours and symbols that represent the musicians you love.

You get offered a chance to “customize your internet bedroom,” which lands you on a download prompt for Verse.

A few lessons for anyone trying to architect more interactive brand moments:

I. Build it where they already are.

This stunt was tailor-made in a laboratory to infiltrate Stan Twitter/Stan TikTok. Verse did post examples of the web app on their own socials, but it seems the real virality began from seeding the experience on various pop culture fandom accounts, which then led to people organically posting the experience themselves.

It’s a good reminder you never really have to start from zero when you’re spreading an idea. Hijack existing symbols or audiences, what MSCHF refers to as “cultural readymades,” so that other authority figures or in-groups do the heavy lifting for you. Read more about designing a contagious stunt here.

II. People love to be told who they are.

Astrology, Tarot, personality tests — they all hand you an artifact with a novel perspective or categorization on who you are. We’re all scavenging for proof that we’re special little snowflakes.

Spotify Wrapped, the canonical modern example of this, effectively just has us promoting their product as a way of promoting ourselves. There are a ton of derivatives of the Wrapped format, from Goodreads to Substack, but they mostly miss the mark. People don’t want data on themselves. People want stories about themselves. Verse used users’ listening history as a proxy for what kind of person they might be, and then packaged that aesthetic into a visual form. It’s the sort of absurd internet catnip that people love to share, whether it ends up being accurate or not.

III. Bridge the gap.

It sounds obvious, but it’s worth underlining: a useful top-of-funnel lead magnet has to actually be representative of your bottom-of-funnel product. It makes no sense to send people a free PDF on how to sleep better and then try to upsell them on a t-shirt brand. There’s a whole host of reasons why ragebait doesn’t accrue any useful version of attention, but if I had to distill it down to one, it’s because it is not representative of the actual experience you’re trying to sell.

I’m excited about the idea of web apps as a lead magnet, because they can be a more accurate proxy of the final experience, especially when compared to a PDF that has no opportunity for participation. Verse’s Internet Bedroom, for example, ends with a clear next step to “download the app to edit your digital bedroom.”

It’s a clear bridge that takes you from “this is the teaser,” to “I know what I’m getting with the entire experience.”

Within a few weeks, 8 million people had tried the Internet Bedroom, and 160k of them installed the app. Who knows how retentive the users were, but I suspect that’s more of a product problem than a marketing problem.

There are a few other examples of interactive stunts like this, such as They See Your Photos (which gives you a great sharable artifact) or Umax (which could’ve done their face scan via a webapp instead of in the app itself.) But this type of micro experience is an arbitrage when the rest of the consumer app industry is still milking Jenni AI’s (fantastic) UGC playbook from 2023.

If scaled UGC content is something of an internet-native teaser trailer for your app, then Verse’s Internet Bedroom is more like an internet-native gateway drug.

Thanks for reading! I write about branded entertainment, exploring how brands and startups become media companies.

Just a reminder that there’ll be no Thursday post this week because of American Thanksgiving. I will instead be busy on my short-form video thinkboi grind.

I think this specific example is a grift, but it’s a good illustration of how hardcore internet marketers — real degens, not tech industry marketers — will try to squeeze value out of vibecoding.

It’s unclear, but Verse is either now defunct or has pivoted to Housewarming.